At the rental agency in Pittsburgh, I saw a woman trying to explain to a student (in English) where he needed to go in order to get settled into his new apartment. The woman kept explaining the directions over and over again in simple Engish so the young gentleman could understand. She used hand movements and gestures and you could see the effort she was making so that the gentleman would understand. He kept repeating words but it was obvious that there was some communication error. It was inevitable that she would feel frustrated.

When the gentleman and his companion left, I smiled at her and said, “language barrier?” “Yes. He literally just got off the plane. From Korea.”

Just got off the plane!

I am an immigrant again.

**** 1989.

Ben-Gurion airport in Israel is filled with people holding signs. People shout in Hebrew and I quickly leave the noises of the crowd. The target? To get my immigrant card, teudat oleh.

I pass a small barricade of Ethiopian newcomers and soldiers in green and grey uniforms. I stop by a newsstand to get a Snickers bar. I will buy the last tangible “connection” I have to the States. I notice the back of the wrapper is in Hebrew with just a few words in English.

At the Ministry of Interior, people push and shove and argue in Hebrew. I stand back and watch Russian and Ethiopian immigrants fight their turns out like gladiators.

Don’t leave the airport until you get your teudat oleh, my father said emphatically.

I don’t want to fight it out, but I realize that I don’t have much of a choice.

When my turn finally comes, I’ve bitten my nails so much to the core that they bleed. Words stay bubbled in my throat. I hold the papers from the Jewish agency and thrust them to the lady behind the counter, while other immigrants crowd around me. I have no space. I need air. I can’t breathe. I want to take a broom and sweep them all away.

The buxom white haired woman who is surrounded by papers says, “you need to go to the Tel-Aviv office,” and scribles something on a small piece of paper.

I pretend to look dumbfounded.

–What? I say in Hebrew. –What you need is not here, she says. –Why not? –Immigrants who are going to the army, go to another office. –But nobody told me that. -Well, I’m telling you.

Dorit, Keep asking the same stupid questions, until you get what you want.

Other immigrants start squeezing their way to the front of the line; they sense that my conversation is over and I am already finished. I hog the space.

I’m now Dorit in Israel, not the American Dorit. Even my five letter name makes me feel little.

Speak fast, grunt, communicate, yell, shout – do what you need to do to be heard is my raging cry.

But my inner protest doesn’t last long and I surrender myself to the crowd. I quickly find a taxi and make sure I hold the “coupon” I have from the Jewish Agency that entitles me to my free ride. Something from nothing. I quickly find a taxi and give him the coupon.

“Where do you want to go?” the taxi driver says in English. It’s obvious he knows I’m a new immigrant. What he doesn’t know is that I am on my way to join my new garin, group of new immigrants, in the middle of the Negev Desert. Together, we’ll get inducted in the Israeli Defense Forces in just a few weeks time.

“Kibbutz Retamin.”

“Where’s that?”

“In the Negev Desert.”

“That’s a long way,” he says.

He looks straight in the distance. I only hope he won’t decline the trip and cause any problems.

He thinks it over. “Okay,” he finally mumbles. “Get in.”

Drops of rain start accumulating on the window.

The driver doesn’t turn on his windshield wipers until there is a thick layer of dust and rain. it takes eight full cycles to wash it all away.

He starts the engine and I lean back. We pass the American tourists pointing and waving to a man with curly black ringlets. He looks like my father minus the tired looking face and the big orange flip-flops.

The driver slowly turns the wheel and we pass border control, the Israeli flag and the welcome sign in Hebrew and I don’t look back.

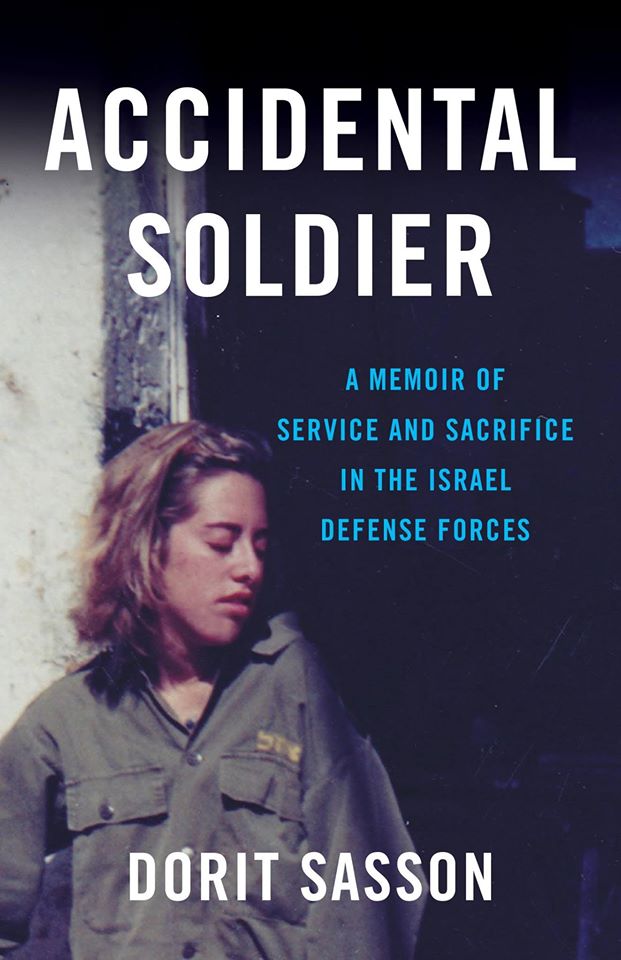

Following three years of serving in the Israeli army as a career officer, Dorit Sasson completed her BA and MA degrees in education and English literature in Israel, and soon after, began teaching English to Israeli schoolchildren in development towns and at kibbutz schools. In 2007, she left with her family to the US where she currently resides in Pittsburgh. Dorit is the co-author of the book, Pebbles in the Pond: Transforming the World One Person at a Time and is currently writing her memoir. She has become a sought after motivational speaker. You can contact her for more details by clicking here .

Connect with Dorit