Once I’m outside Ben Gurion airport and without my immigrant card, I try to remember what I’m supposed to do. Luckily, I have kept the letters my Dad and stepmother telling me about the brave decision I did to leave Mom and New York City. These letters are kept super close in my side pants pockets and for some odd reason, I believe they will help me make the right decision. (They are creased from being folded many times over.) I debate my next steps:

Once I’m outside Ben Gurion airport and without my immigrant card, I try to remember what I’m supposed to do. Luckily, I have kept the letters my Dad and stepmother telling me about the brave decision I did to leave Mom and New York City. These letters are kept super close in my side pants pockets and for some odd reason, I believe they will help me make the right decision. (They are creased from being folded many times over.) I debate my next steps:

1. Use the free taxi voucher from the Jewish Agency

2. Find a taxi stand and speak your best Hebrew

3. Decide whether I want to go straight to the kibbutz or to see my Savtah (grandmother)

4. Lug my blue suitcase I bought on 14th street and 8th avenue for twenty bucks by pulling on a piece of fabric.

The third decision is the hardest. If I make the extra 3 hour plus journey to the kibbutz listed on my Jewish Agency papers to join the group of other young immigrants from around the world who have come to volunteer for the Nahal division of the Israeli Defense Forces, I might risk overtiredness.

But, it also means I will have to make a huge effort to “get out of my New York City skin” and step away from my mother’s voice of fear and paranoa that managed to suck me in. Fear of not taking risks and making good decisions. Sticking to the agenda. Eaten up by fears of getting pushed into a subway track or getting pickpocketed by strangers. Of course, I knew better. But now, all that seems so far away.

In short, the decisions of the next twenty four hours are crucial and could determine a “make or break situation.”

I may even surprise myself for not following through with my plans, and get back on a plane to New York City.

I am anxious, eager and excited. I want to know already if the 45+ year old kibbutz in the middle of the Negev Desert I have painted in my mind really matches up to what I will soon see in reality.

Physical exhaustion outweigh the emotional benefits.

If I go to Savtah’s place in the suburb of Givatayim, 30 minutes away, I will have to pay for the bus ride itself. I have no idea which bus to take and how to get to the Central bus station from Savtah’s place.

For an eighteen year old, this is a big decision. And a big deal.

I also want to put it off.

Because the whole situation will be easier to deal with IF I put it off.

Now, lying on my mother’s loft bed in our Greenwich Village artist residence in New York City, I wait for mom to come.

She said she would come after she finished practicing for her big gig.

The cracks on our wavy 15 feet loft ceilings resemble the same rabbit I had seen many years ago when I slept in-between two parents when the cracks on my wavy ceiling became too terrifying in the dark.

Now, I have the bed to myself.

Dad has moved out several years ago. It’s 1988. He’s taken his art with him including the stained glass oval window above my doorway, one of the twelve themes associated with the Twelve Tribes of Israel my father was commissioned to create for a synagogue in Queens, NY. There are no multitudinous swirls of blues, oranges, reds and greens – his favorites. Many years ago, I would try to figure out how this particular window is part of a Jewish “theme” and settle on discovering shapes instead. Like every night, I fixate on a blue and orange shape that resembles a foot and leg. Years later, my father removed this stained glass window when he relocated permanently to Israel with my stepmother and younger brother. All that remains is a thick circle piece of wood. I avoid sleeping in my loft bed alone and have taken up a new residence in my mother’s bed.

Her footsteps are heavy.

Finally.

She lies next to me and I reach for her cold hand.

With my eyes still fixated on the ceiling, I blurt out, “Mom…I’m scared.”

Silence.

“Hey Mom… I’m scared.”

“What’s wrong honeybun?”

She says “honeybun” in the same demeaning, fake sounding voice she has been using for years, but only now, I am waking up to how it really sounds.

“I just don’t know what I should do.”

Mom doesn’t ask me questions, so it’s up to me if I want to make something of this.

“Mom, I don’t know what I want to do with my life.” I say.

“It’s okay, hunny bunny.”

I let go of her hand. But just for a while.

I know what I’m asking.

The fact she cannot really help me means that maybe I need to experience life on my own for a while and not go the Mommy route. Maybe I can just manage without asking her.

Now that I’m on my own, there’s no-one for me to say, “Oh my goodness – what unbearable heat!” in English. And I can’t exactly go back to New York City.

I brush my hands under my armpit and feel the sweet sweat. Good god, I think. Did I really have to leave my Mom and New York City to feel a sense of emotional independence? I mean, why couldn’t I just stay in comfortable New York City – Damn it!

I look at the palm trees lining the roads and watch as other planes land and take off. I am still in transition.

There’s army soldiers everywhere, each with different tags indicating their units walking with what could be their grandparents. I find this scene odd. Soldiers at an Israeli airport and in such large numbers? Maybe one of them will be me some day.

Right away, there’s something about this land: its accessibility, pregnant with possibilities. I am just a few hours from donning an army uniform.

At once, I knew the humidity and mugginess of the Israeli climate were with me to stay. And I walk to the taxi stand just meters ahead of me to the already long line of immigrants and tourists.

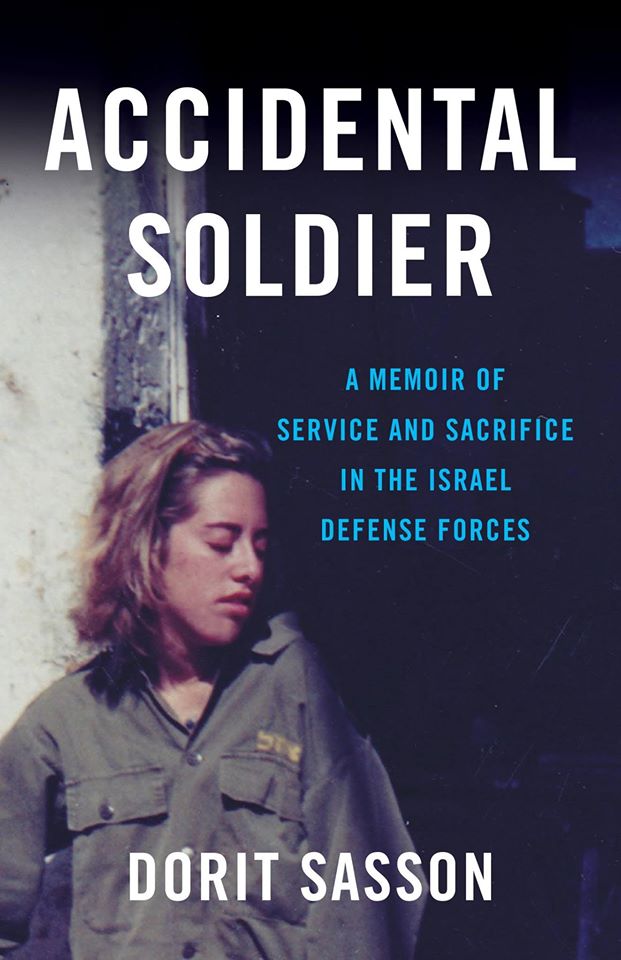

To read other installments about this memoir, click here. To read the “story” behind the memoir, click here.

You brave woman!!!!!!!!!!!!

Thank you so much, Jennifer, for commenting. I so appreciate it.

Dorit