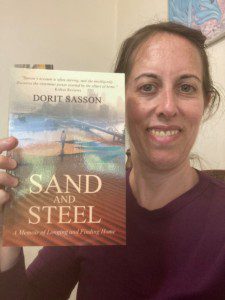

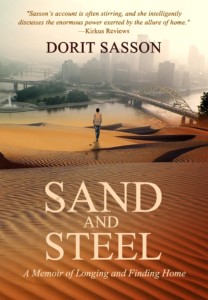

Earlier this year, Linda Feagler, veteran writer and editor of Ohio Magazine did an oral interview with me about my newly released memoir Sand and Steel: A Memoir of Longing and Finding Home. I time-traveled with her through military bases, and service on kibbutzim, and finally back to the United States. In our interview, I share why I love Israel, what my time with the IDF taught me, why I am grateful for the experience, and what being back in America means to me right now.

On August 14th , my beloved father Ahron Elvaiah of blessed memory passed away from complications of COVID, so I am dedicated this interview to his memory. In the interview, you’ll learn a bit more about him.

Dorit Sasson was at a crossroads. Feeling like a stranger in a strange land and struggling to distance herself from an overbearing mother, the 19-year-old left her parents’ home in New York’s Greenwich Village and headed to Israel, where she lived on a kibbutz and joined the Israel Defense Forces, the military for the State of Israel. Like her comrades on the four military bases, she was assigned to, Sasson risked her life to protect Israel’s independence while upholding human dignity and respecting the values of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state.

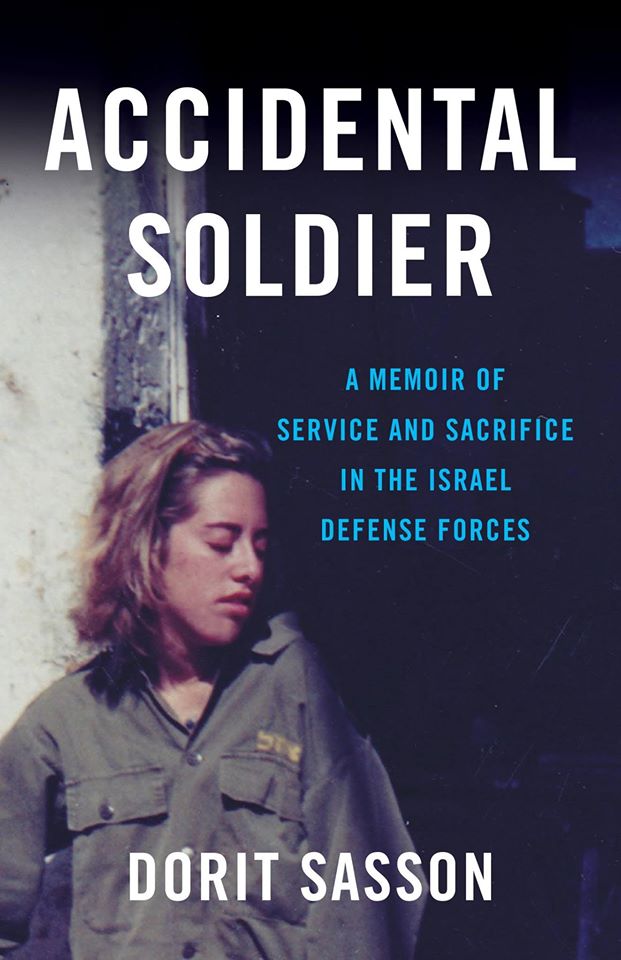

In 2016, the author — who lives in Pittsburgh with her husband and two children — published Accidental Soldier: A Memoir of Service and Sacrifice in the Israel Defense Forces, of her three years of service, as well as her life in Israel that spanned 1990 to 2007. Sasson, 50, shares her story about returning to America in her new book, Sand and Steel: A Memoir of Longing and Finding Home.

What led you to write “Sand and Steel”?

What led you to write “Sand and Steel”?

Writing the first memoir, Accidental Soldier took a lot of guts. I wrote the second one because when you’re living with the bigger-than-life displacement I felt, you have a choice: you can continue to live it or you can continue to write about it so you can process it and understand that it is no longer a burden. I’ve discovered there are many expats like me who suffer from reverse culture shock. Writing Sand and Steel has been very healing for me, and I hope it will help others who feel as I do.

What is the significance of the title?

My story is Pittsburgh in nature, but it’s also uniquely Israeli. Pittsburgh is known as “The Steel City.” Steel is not flexible and withstands high temperatures. Sand, on the other hand, is moldable and flexible. It is my way of addressing both cultures and bringing them together.

You were born in New York, but your bond to the state of Israel is strong. How was it formed?

You were born in New York, but your bond to the state of Israel is strong. How was it formed?

My father was born in Jerusalem in 1937. He served in the Army but was always interested in pursuing the arts. He was awarded a Fulbright to study art in Rome, where he met my mother, who was born in Valencia Spain in 1936. She and her family had escaped the Nazis and immigrated to the United States via the Panama Canal and ultimately, opened a dry goods shop in the Bronx. My mother was a child prodigy who became a pianist. She was also in Rome on a Fulbright when she met my father. They found their way to the United States to pursue their careers, moved to New York’s Greenwich Village, and flourished as artists.

What captivated you about Israel?

What captivated you about Israel?

Because I had a native Israeli father, I felt a little special — and [in America], I also felt like I was a minority in a minority culture. That enticed me to want to go and check out Israel. But the compelling reason was I had a place to go: My aunt was a kibbutz member, and we would travel back and forth from Israel to the states to see each other.

Your family traveled from Greenwich Village to Israel during summers. What was it like living in two different worlds?

Your family traveled from Greenwich Village to Israel during summers. What was it like living in two different worlds?

Greenwich Village, like the whole landscape of New York, is known for its bohemian lifestyle. [As I got older], I realized there was a life beyond the building we lived in, that there’s a place across the ocean called a kibbutz. When we visited, I saw there was no hierarchy. People worked together for the benefit of each other, and no one received more than anyone else. Whatever money was made went to the kibbutz, not individual members. And in return, the kibbutz paid for the basic necessities that a person needed to live. Since we’re talking the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, it was very much a socialist utopia, and there was something emotionally freeing about that, along with a warm acceptance of everyone. When I made those first trips, I got the impression this was a place to break boundaries. When I got older, I made trips back there to volunteer. It was a way to escape my mother and gain emotional independence.

How did the relationship with your mother influence your decision to leave New York?

How did the relationship with your mother influence your decision to leave New York?

My mother was fearful of many things. She would pull me away from the TV set every time there was a story about Israel — sometimes covering my eyes, and sometimes turn it off. It was clear she hated Israel and was afraid of the terrorist attacks that took place there. My father, on the other hand, never missed a chance to connect with his homeland. My mother’s fears and her desire to control my life were the tipping point. I had my own idea of what I wanted to do with my life. I didn’t want to be in the college scene — that was for sure. Instead, I wanted to be more self-directed and find my purpose, and life on a kibbutz appealed to me. My father encouraged me to pursue my own life. He told me that if I stayed in New York City, I’d become exactly like my mother.

What duties did you perform at the kibbutz?

I wore different hats over the years as I moved from kibbutz to kibbutz. I was in the IDF’s Nahal unit, which basically combined military service with agrarian work. I also had chores that ranged from helping out in the dining room to doing laundry. Basically, anything that was needed, I’d be there to help with.

Did you have any fears about joining the Israel Defense Forces?

Did you have any fears about joining the Israel Defense Forces?

Danger was all around, but I caught on very quickly that Israel is a country that has your back. People look out for each other in ways that Americans don’t. There’s a big brother/big sister mentality that might feel intrusive in America, but in Israel, people realize the intention is to demonstrate that we care. When I picked up on these feelings, it softened my decision to join, because I hadn’t experienced this in America.

What is the IDF training program like?

What is the IDF training program like?

If you’re a new immigrant, you enroll in a special Ulpan Hebrew language course so you can really up your knowledge of Hebrew culture and the military. In addition to becoming or staying physically fit, you have to demonstrate you work well under pressure, particularly how you work in a group because you need the group in order to survive. It’s a survival-of-the-fittest type of mentality. The training period for women is about a month. It’s longer for men. Basic training culminates in being awarded your beret and your tags.

I achieved the rank of lieutenant.

Did you experience heart-stopping moments?

One of the early ones took place when the Persian Gulf War started. We were close to the Lebanese border, and my job was to keep track of all the soldiers who entered and left the base, no matter the reason. There were no computers back then — everything was done by hand and entered in a ledger. When they left and didn’t come back, I was always worried something might have happened to them. There was one soldier in particular who never returned. I found out later it was a medical issue, not a military one — which was a great relief. And whenever bombs went off, you never knew whether it was a training exercise or the enemy approaching. I wasn’t privy to everything that was happening, but I knew we were in a very strategic spot and were exposed.

After your term of service was up, did you always plan to return to the United States?

No. I really felt I had bought a one-way ticket to Israel. I was a new immigrant who wanted to stay committed. The test of the IDF was to see how well I could create a home and have an established lifestyle. The small intimate country claimed me, and it brought out the best in me in ways I will always be grateful for. After my term of service ended, I attended the University of Haifa, received my B.A. and M.A. degrees in English literature, and became an English teacher for Israeli students.

In 2002, you married Haim Sasson, whom you met on your last kibbutz, and have two children, Ivry and Ayala. Why did you decide to come back to this country?

In 2002, you married Haim Sasson, whom you met on your last kibbutz, and have two children, Ivry and Ayala. Why did you decide to come back to this country?

In 2000, life on the kibbutz really started to change. People wanted to make their own money, buy cars, and travel abroad. They wanted to have a materialistic life. And whenever you have that, it completely destroys the socialist commune. It went from “us, us, us” to “me, me, me.” When the kibbutz turned into a moneymaking machine, things began to crumble. Haim had an extremely important job as the procurement manager of the dining room. But when the kibbutz was no longer a kibbutz, he was thrust into a new way of life, and we struggled to make ends meet. My husband, who speaks four dialects of Arabic and has a very high IQ, was forced to jump from one blue-collar, low-paying job to the next.

Was it an easy decision to make to return to the United States in 2007?

Was it an easy decision to make to return to the United States in 2007?

It was a heart-breaking one. Our kibbutz was located on the Jordan River with a beautiful view of Mount Hermon. We tried to make staying there work, but we just couldn’t. We learned the sad reality that Israel does not like to employ older people. There were a very limited number of industries where age was not a barrier.

Why did you decide to settle in Pittsburgh?

We chose Pittsburgh, because we heard a lot of good things about the Jewish community there, and we are not disappointed.

Were you nervous about returning to America?

Yes. There is a reverse culture shock and we knew we had to figure out how we were going to fit in. There was so much emotion in making that decision, and so much was at stake when it came to starting a new life.

What were some of the biggest adjustments you had to make?

Coming from Israel, I was used to a very traditional and social culture that lives in the moment and is very spontaneous. People don’t schedule play dates there as they do here. That was a big transition. Other reverse culture shock examples included not knowing what an SUV, Target, or Costco was. Although Israel is very Americanized and has outdoor malls, they don’t have brand names.

Where does your new book “Sand and Steel” begin?

Where does your new book “Sand and Steel” begin?

The book begins in 2006 at the start of the Second Lebanese War, and the decision we made that it was time to leave.

As the subtitle implies have you found home? I’ve learned home is not necessarily limited to a place — it’s who you are. As a result, the concept of home is always changing. And the longing will go away because I’ve turned my kitchen into an ex-pat kitchen making traditional Israeli foods for Haim and our children. We also celebrate Israel Independence Day and other holidays America does not celebrate.

What’s next for you?

I am currently thinking about toying with the short-story genre. I need to stop writing about myself because it’s quickly getting exhausting.

Connect with Dorit